Nasty is the New Black

Nasty is the New Black

James Souttar

This article was originally published on Medium, 9/6/2016

The dark heart of the emerging workplace

Over the last couple of years we’ve all seen politics turn distinctly nastier. Whether it’s the abusive rhetoric of Donald Trump, the Maoist-style ‘calling out’ by campus protestors, the paranoiac accusations of media conspiracy against Bernie Sanders or Jeremy Corbyn, or the barefaced lies of the ‘Leave’ campaign, few of us have witnessed anything like this before. But these disturbing tendencies are by no means confined to politics. They are increasingly also found in the world of work. Indeed, so phenomenal is the rise of ‘nasty business’ that ideas of corporate citizenship and responsible business are beginning to feel like relics of the last century. Enter the world of the dark brand.

Behold the Uber-man

There are many ways in which business has taken a turn for the worse but, without a doubt, the most noticeable of them is the emergence of the ‘care-less corporation’. This is the transnational company (now frequently a tech ‘unicorn’) which evades taxes, ‘disrupts’ sectors through automation, deskills and casualises occupations, off-shores production, turns a blind eye to what goes on in its supply chain, drives out competitors, is high-handed with customers and autocratic with staff, and is unapologetic for its behaviour. Uber, of course, is the ürphanomen here — casting its malefic influence over numerous acolytes. But Amazon, Apple, Google, Starbucks and others all illustrate this trend in different ways. And Uber’s answer to Donald Trump, CEO Travis Kalanick, best articulates the antagonistic, blowhard attitude of care-less business when he says: “We didn’t realize it, but we’re in this political campaign, and the candidate is Uber, and the opponent is an asshole named taxi”.

The euphemistically named ‘sharing economy’, of which companies like Uber, Airbnb and TaskRabbit are the stars, illustrates some of the most cynical and destructive aspects of care-less business. Uber’s predatory business model has ripped through cities across the world, turning their regulated taxi-cab industries into an unregulated free-for-all, without security for — or responsibility towards — public or employees. As the MIT Technology Review notes: “Uber will fire a driver if his or her performance rating (an aggregate of the ratings provided by customers of that driver) falls below a certain level. Imagine the fear under which an Uber driver operates. Assume that a driver buys a one-year-old Toyota Camry and drives around Boston for 10 to 12 hours a day providing rides. He picks up a bunch of spiteful teenagers intent on dodging the fare, and they ding the driver’s rating because of a routing mistake or just for fun. A few such rides can get him fired. There is no mentoring, training, or improvement program — nothing.” What Uber is doing to public carriage, Airbnb is doing to the private rentals sector and TaskRabbit to the casual labour market. And similar brokering platforms are springing up wherever opportunities are spotted.

Office pathology

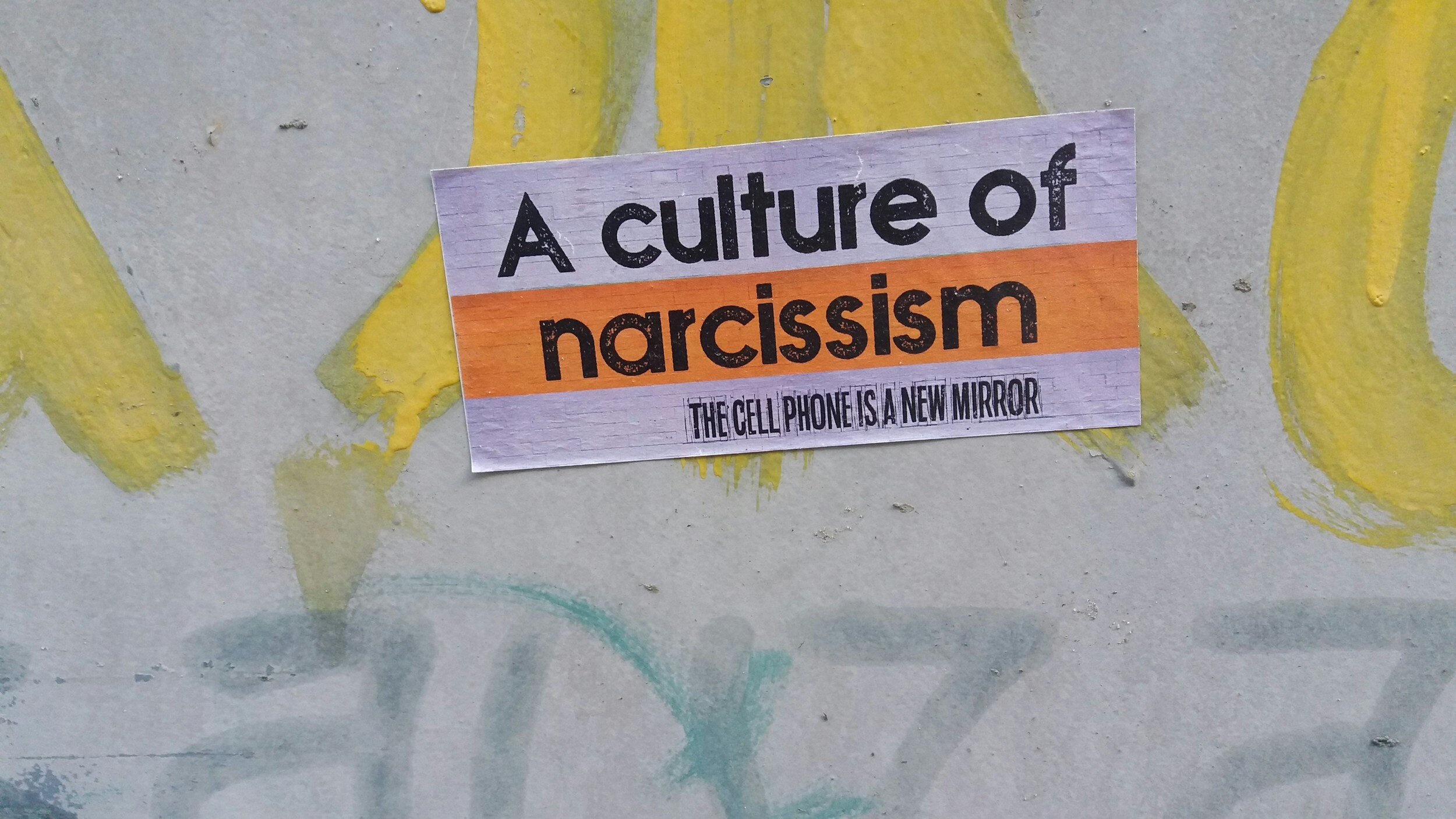

As in politics, this new nastiness has emerged hand-in-hand with the proliferation of a particular psycho-pathology: narcissism. But while many of us are now becoming aware of the ravages of narcissism, business is in two minds about it. On the one hand narcissism, with its frequent spill-over into sexual harassment, workplace bullying, fraud and incompetence, poses a serious risk for organisations. But, on the other, the pantheon of ‘inspirational’ business leaders would be almost bare if all the narcissists were removed. Steve Jobs, for instance, has become the poster-boy for entrepreneurship across a dozen sectors — yet he ticks all of the boxes for Narcissistic Personality Disorder. And his legendary, nightmarish interpersonal skills are now routinely excused on account of his brilliance. Management ambivalence towards narcissism is illustrated by the reaction of the business media. Forbes, for instance, tells us that “Narcissism may be your business’ best friend”, while The Wall Street Journal reports that ‘dark’ personality traits can help people rise through the ranks. “For instance, people with narcissism, who want to be the center of attention, often make a good first impression on clients and bosses’, says a 2014 review of more than 140 studies on people with mild, or subclinical, levels of dark personality traits. “They also can be persuasive when pitching their own ideas.”

At the same time, the rise in narcissism (researcher Jean Twenge cites ‘four cross-sectional, one retrospective, and four over-time datasets’ in support of her claim that narcissism is increasing dramatically in American society) is undoubtedly connected with most of the abuse in, and by, organisations. And we might remind ourselves here of the criteria of pathological narcissism from the American Psychiatric bible, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). According to the DSM narcissists show some or all of these characteristics:

1 | Grandiosity with expectations of superior treatment from others;

2 | Fixated on fantasies of power, success, intelligence, attractiveness, etc.;

3 | Self-perception of being unique, superior and associated with high-status people and institutions;

4 | Needing constant admiration from others;

5 | Sense of entitlement to special treatment and to obedience from others;

6 | Exploitative of others to achieve personal gain;

7 | Unwilling to empathize with others’ feelings, wishes, or needs;

8 | Intensely jealous of others and the belief that others are equally jealous of them;

9 | Pompous and arrogant demeanor.

The Harvard Business Review points out that “Research shows there are a large number of narcissists who become leaders. If you’re unlucky enough to have one of these people as a manager, it may be no consolation that you’re in good company. […] Narcissists have an exaggerated sense of entitlement and require constant admiration. They are quick to claim credit for others’ achievements and blame colleagues for their own failures. They care only about their own success, and they’re willing to take advantage of others to get what they need. In short, they’re incredibly difficult to work for.”

Trapped in a hell-on-earth

In case you were wondering, ‘incredibly difficult to work for’ is code for a nightmarish experience which can have one doubting one’s own judgment. The narcissist is often a bully and workplace bullying is carried out by people with narcissistic or sociopathic tendencies. According to ACAS, the Arbitration and Conciliation Service, workplace bullying is on the rise in the UK. In 2015 the service received more than 20,000 calls about harassment and bullying at work. ACAS’ chair, Brendan Barber, commented: “Callers to our helpline have experienced some horrific incidents around bullying that have included humiliation, ostracism, verbal and physical abuse. But managers sometimes dismiss accusations around bullying as simply personality or management-style clashes…”

Staggeringly, research shows that one in ten workers have been bullied in the last six months, one in four in the last five years, and that 47% of workers had witnessed bullying in their workplace. The impact of workplace bullying is also shocking: 80% of victims reported debilitating anxiety, 52% experienced panic attacks, 49% developed clinical depression and 30% post-traumatic stress disorder. Shame, guilt and an overwhelming sense of injustice are also common consequences.

The response to bullying in organisations has been far from effective. Research published in the Journal of Managerial Psychology found that: “More than half of workplace bullies, 54%, have been at it for more than five years, with no consequences. Some bullies have been with their company for as long as 30 years.” In most cases, bullies outlast their victims — a longevity they owe to ‘often making a good impression on clients and bosses’.

Workplace bullying is nothing new, but in what I’ve call the care-less corporation disregard for workplace bullying is frequently reflected in a dismissive attitude from the very top. As an example, a 2015 New York Times report into working conditions at Amazon revealed: “At Amazon, workers are encouraged to tear apart one another’s ideas in meetings, toil long and late (emails arrive past midnight, followed by text messages asking why they were not answered), and are held to standards that the company boasts are ‘unreasonably high’. The internal phone directory instructs colleagues on how to send secret feedback to one another’s bosses. Employees say it is frequently used to sabotage others. (The tool offers sample texts, including this: ‘I felt concerned about his inflexibility and openly complaining about minor tasks’.) Many of the newcomers filing in on Mondays may not be there in a few years. The company’s winners dream up innovations that they roll out to a quarter-billion customers and accrue small fortunes in soaring stock. Losers leave or are fired in annual cullings of the staff — ‘purposeful Darwinism’, one former Amazon human resources director said. Some workers who suffered from cancer, miscarriages and other personal crises said they had been evaluated unfairly or edged out rather than given time to recover.”

Responding to this story, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos’ replied: “The article goes further than reporting isolated anecdotes. It claims that our intentional approach is to create a soulless, dystopian workplace were no fun is had and no laughter heard. Again, I don’t recognize this Amazon and I very much hope you don’t, either.” Practices that were documented and evidenced are swept away by Bezos under the pretext of being unrecognisable to him. And given the nature of the Stasi-like culture the Times described, Bezos’ “I very much hope you don’t, either” begins to assume an ominous Big-Brotherly ring.

Cult-like cultures

When writer Dan Lyons joined marketing software startup Hubspot, it was to write the company’s blog. But after what he found there, he wrote a book: My Year in Startup Hell. “At HubSpot, employees abide by precepts outlined in the company’s culture code, a document that codifies HubSpot’s unusual language and sets forth a set of shared values and beliefs. The culture code is a manifesto of sorts, a 128-slide PowerPoint deck titled The HubSpot Culture Code: Creating a Company We Love.

“The code’s creator is HubSpot’s co-founder. Inside the company he is always referred to simply by his first name, Dharmesh, and some people seem to view him as a kind of spiritual leader. Dharmesh claims it took him 100 hours to make the slides. He sent me a link to the slide deck a few days after I interviewed with him and his co-founder, Brian Halligan, I suppose as an inducement to join the company. He said it was a slide deck that ‘describes HubSpot’s culture’.“The code depicts a kind of corporate utopia where the needs of the individual become secondary to the needs of the group — “team > individual,” one slide says — and where people don’t worry about work-life balance because their work is their life.

“The culture code asks, ‘What does it mean to be HubSpotty?’ and then defines the meaning of that term, explaining a concept that Dharmesh called HEART, an acronym that stands for humble, effective, adaptable, remarkable, and transparent. These are the traits that HubSpotters must possess in order to be successful. The ultimate HubSpotter is someone who can “make magic” while embodying all five traits of HEART. ‘Dharmesh’s culture code incorporates elements of HubSpeak. For example, it instructs that when someone quits or gets fired, the event will be referred to as “graduation”. In my first month at HubSpot I’ve witnessed several graduations, just in the marketing department. We’ll get an email from Cranium [HubSpot’s former Chief Marketing Officer, Mike Vulpe] saying, ‘Team, just letting you know that Derek has graduated from HubSpot, and we’re excited to see how he uses his superpowers in his next big adventure!’ Only then do you notice that Derek is gone, that his desk has been cleared out. Somehow Derek’s boss will have arranged his disappearance without anyone knowing about it. People just go up in smoke, like Spinal Tap drummers.

“Nobody ever talks about the people who graduate, and nobody ever mentions how weird it is to call it ‘graduation’. For that matter I never hear anyone laugh about HEART or make jokes about the culture code. Everyone acts as if all of these things are perfectly normal.”

Lyons’ book describes a corporate culture that is uncannily reminiscent of the religious cults of the 1970s. It’s a type of culture that is becoming increasingly common, especially for innovative, entrepreneurial, ‘disruptor’ companies.

In his classic work on cult behaviour, The Wrong Way Home, University of California Professor of Psychiatry Arthur Deikman identified four defining characteristics of cult-like organisations: obedience to authority, compliance with the group, avoidance of dissent and devaluing outsiders. In the short excerpts from Lyons’ book above, we can see all of these strongly evidenced: the reverence of Dharmesh, the prioritisation of the team over the individual, the lack of any cynicism or humour about the company code and the indifference to the disappearance of those who have been dismissed. The creepy euphemistic language further reinforces Hubspot’s cultishness.

The greatest concern about cult-like workplaces must be the way in which Deikman’s four factors combine to create situations in which individuals come to believe that the group’s purposes transcend social norms, legitimate otherwise unconscionable behaviour, and encourage distorted, unrealistic thinking. Without the robust challenge of dissent, unquestioned platitudes, like Dharmesh’s HEART, become truths, and a ‘reality distortion field’ extends through every activity. In such situations there is literally no limit to what a person is capable of doing in the belief that it is required. As Deikman puts it: “Characteristically, cults subordinate ethical and moral standards to the particular aims of the group and leader. These are called higher purposes, usually put in terms of saving the world.” [Which was how Steve Jobs famously proposed to John Sculley: “Do you want to sell sugared water for the rest of your life? Or do you want to come with me and change the world?”]

The last word on these cult-like companies, however, should go to Lyons, talking to the New York Post. “HubSpot’s leaders were not heroes, but rather sales and marketing charlatans who spun a good story about magical transformational technology and got rich by selling shares in a company that has still never turned a profit.”

Post-factual communications

Political campaigning, on both sides of the Atlantic, has recently veered towards such economy with the truth that it almost feels like a new form of austerity. Fact checking websites chalk-up politicians’ numerous lies, but the politicians themselves remain unrepentant — and undeterred. Facts, along with experts, have become old hat. It should come as no surprise, then, that complaints about mendacity in corporate communications are also on the rise.

In 2015 the UK’s Advertising Standards Authority insisted on changes or withdrawal of a record 4,584 advertisements (most surprising was the increasing number of complaints about charities, who are by no means immune to any of the tendencies I’ve described). 2015 also saw the a record fine for making false claims in the US. Lumos Labs, the company behind the brain-training application ‘Lumosity’ was fined $2m for making fraudulent claims and preying on consumers fears, and issued with a $50m penalty for harming consumers.

Dishonesty is becoming more common among staff, too. A feature in Stylist Magazine records: “A study of 2,000 Britons found that on average people lie 28 times a month through email, social media and mobiles, compared to 17 times face-to-face. With much of our work being conducted remotely, this is increasing lying in the workplace by over a third. A University of Massachusetts study confirms this, finding that people told five times as many lies over email as people speaking face-to-face.” According to Robert Feldman, professor of psychology at the University of Massachusetts, “We’re seeing a kind of cultural shift where we’re lying more. It’s easier to lie and in some ways it’s more acceptable.”

And where dishonesty becomes institutionalised, an even more disturbing pattern emerges. For instance, while investigating the running of a GP out-of-hours service in Cornwall by the multinational service company Serco, the House Of Commons Public Accounts Committee found that data had been falsified, there was a culture of “lying and cheating”, and the company had falsified figures on its performance 252 times. These failings only came to light thanks to whistleblowers, who were treated in a way that MPs considered “bullying and heavy-handed”.

In my paper A Crisis of Trust I listed 30 recent high-profile corporate betrayals. Every one of the institutions listed is a household name. And in every case the organisations involved responded to initial accusations — which subsequently turned out to be correct — with denials, dissimulation and lies.

The dark heart of the emerging workplace

How did organisations become this dysfunctional? That’s a question that I can’t do justice to here, but which I ask myself repeatedly. Somewhere between the upbeat optimism of the late 1990s — which saw the birth of ‘responsible business’ (and such initiatives as the RSA’s ‘Tomorrow’s Company’) — and the 2007/8 financial crash, we lost our way. The seeds of the care-less corporation were sown in the early years of this millennium, as increasing cynicism and exploitation gave us churning markets, zero-hours contracts, unpaid internships, wage stagnation, offshoring, and a race to the bottom in the supply chain. We all started to care less. And the idea of ‘living the brand’ and of ‘brand religion’, which form the basis of the cult-like company, also came to the fore in this period as a substitute for the human values which were disappearing.

The different aspects of ‘nasty business’ that I’ve identified here are intertwined. Common to all is the narcissistic personality type, whether as ‘disruptive’ entrepreneur, bullying manager, cult leader, conscienceless executive or dishonest communicator. As Professor Twenge identified in her book The Narcissism Epidemic, narcissists are more common than ever before. However they are disproportionately prominent in organisations as a result of recruitment, retention and advancement policies which favour them. The corporation has made a Faustian pact with narcissism, in the belief that it can make the reality distorting individual work for it. It’s a pact I think we will come to regret.